5 Minutes With Gartner's Senior Director, Koray Köse

What impact does a crisis such as war have on the procurement and supply chain industry, particularly when these functions are more interlinked and interdependent than ever before?

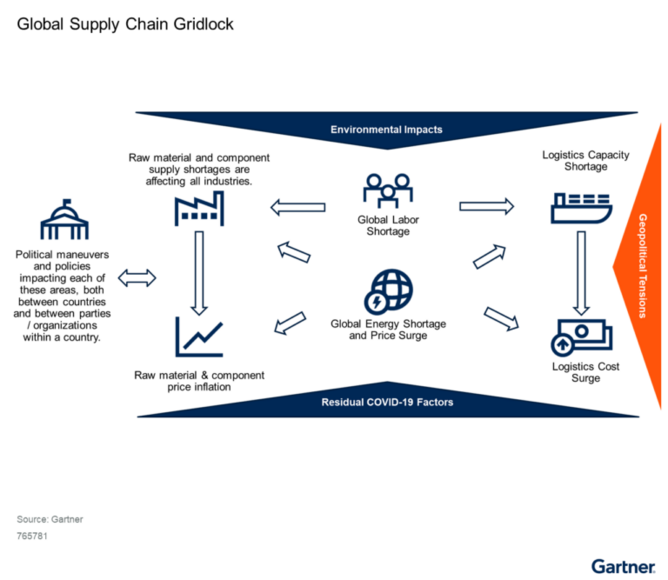

Globally complex geopolitical and economic dependencies and other unresolved tensions can severely impact global trade and further complicate the supply chain gridlock that economies started to experience in 2019. Ongoing imbalances and the global supply chain gridlock require companies to stay on top of the emerging issues that vary, from impacts on costs to nonavailability of materials, logistics and changing legislations. Reverberations are already being felt. Given the volatility of events — pandemics, inflation, energy supplies, war and more — the ability of the enterprise to detect rapid shifts in information and then act on it quickly is of utmost importance. It is now intolerable for one department to ‘sit on’ information and slow its dissemination throughout the organisation to ensure all can respond to the same information, at roughly the same time, with the same sense of urgency. So, there are no two separate functions – procurement and supply chain. Procurement is supply chain is procurement.

What has history shown us when it comes to preparing and responding to situations such as these?

Most organisations have focused on risk mitigation rather than risk management and often created more exposure and vulnerability by doing so. Risk management is a holistic view of the organisation’s activities, risk appetite, risk capacity and vulnerabilities. Risk mitigation, however, is much more single-issue focused and reactive in nature trying to solve specific risk events or vulnerabilities one by one. This created fragile supply chains without supply ecosystems developing towards higher purpose over time. Those supply chains can be stuck in cost efficiency stages - or worse even in long term single or sole source chains. Events of the last few years have created significant impacts operationally but carry a bigger issue that is impacting strategic objectives like profitability, market share, competitive position and share price. Strategic performance indicators are harder to recover and often require significant additional investments that add to the opportunity costs.

What are some other modern challenges that procurement and supply chains need to consider?

Many organisations struggle with having insights and visibility into their supply chain. The 2021 Gartner Supply Chain Risk and Resilience Survey found that visibility improvements were among the top three most important areas of improvement to supply chain risk management at 70% (and 83% among enterprises that have revenue above US$1bn). 40% of respondents mentioned visibility as the top area of improvement. This is based on the lack of a complete view of the supply network. Only 53% of companies have at least 90% insights into their Tier 1 suppliers. That drops to merely 4% of companies achieving a 90%+ visibility for Tier 2 and only 3% of companies claiming this level of visibility for lower tiers. Investments into people, processes and technologies that enable better supply chain visibility, information gathering, analytics (including a strong focus on leveraging advanced analytics, predictive and prescriptive) and decision making will be the differentiators of a successful — or failed — risk-management initiative. A well-defined response strategy is critical to get ahead with short, mid and long-term action plans for this and future risk events.

What short-term, mid-term, and long-term recommendations would you suggest to the procurement and supply chain industry?

Short-term: Immediately start creating first-tier visibility into the existing supply networks in order to evaluate potential risk exposure and determine vulnerabilities. Follow through with n-tier visibility, although results will likely only be visible midterm to long term. This is key to enabling effective response strategies. The event implication can span much further than direct supply chain ties into the conflict region. It is critical to find the best options to get around potential obstacles and to make timely and tough decisions that will keep your organisation moving forward.

Mid-term: Continue to commit and secure volumes as a risk response for the most fragile supply chains, including inventory, manufacturing capacity and labour. Diversify sources and routes where possible. Evaluate the ‘catastrophe on top of a catastrophe’ scenario and go beyond the initial direct impact and down to the raw material level even outside of the region.

Long-term: Increase resilience in high-value, at-risk, concentrated supply networks by deploying strategic redundancies that drive competitiveness and cascade down.

What impact can already be seen in procurement and supply chains?

Supply chain leaders should brace for ‘a catastrophe on top of a catastrophe on top of catastrophe’ beyond what we have experienced thus far from trade wars, COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine. Continue to commit and secure volumes as a risk response for the most fragile supply chains, including inventory, manufacturing capacity and labour. Diversify sources and routes where possible. Evaluate the ‘catastrophe on top of a catastrophe’ scenario and go beyond and down to the raw material level even outside of the region.

Among other critical commodities like metals and hydrocarbons, Ukraine and Russia produce 30% of the world’s wheat supply, 20% of its corn supply and 80% of its sunflower oil, with much of it going to countries in Africa and the Middle East. Intra-African trade is also limited in scope to replace imports from Russia and Ukraine. Regional supply of wheat is not significant with other complexities like the lack of efficient transport infrastructures and storage capacity. Increased costs of fertilisers like urea and phosphate and energy shocks for energy-intensive inputs increase further pressures for global supply chains. Prices for wheat, corn and barley have recently soared so much that even higher price producers like India are now competitive in the global grain export market for the first time after 2012, a year that Russia and Ukraine suffered from a severe drought.

Putting this into context with country-specific dynamics like corruption, climate change, export restrictions and irrational buying, food insecurity is the ticking time bomb that will quickly turn into the most important raw material crisis yet stemming from the most fragile regions by summer/fall 2022.

This is a seismic shift in globalisation that will not revert back to pre-invasion global supply chains. Multi-polarisation, that isn’t yet defined well in many value chains based on composable and fluid supply ecosystems will dominate the future in supply chain.

- ExxonMobil Procurement: Inclusive Sourcing & SustainabilitySustainability

- TotalEnergies: Playing a Key Role in Sustainable ProcurementProcurement Strategy

- SAP and Deutsche Telekom Collab Revolutionises ProcurementDigital Procurement

- Nike Exceeds US$1bn Diverse Supplier Spend Two Years EarlyProcurement Strategy